Legal liability for AI-driven decisions – when AI gets it wrong, who can you turn to?

Given the rapidly increasing integration of artificial intelligence models (AI) into traditional industries and businesses globally, in this article we explore some of the questions relevant to the issue of liability for losses arising from AI-driven decisions, with a particular focus on the energy, resources and commodities sectors.

Background: the increasing integration of AI into businesses and decision-making processes

AI is becoming increasingly integrated into global supply chains and businesses around the world. The IBM Institute for Business Value has observed that more than 40% of CEOs already rely on generative AI to inform their decision-making processes – and some decisions are being made entirely by AI. For example, the World Economic Forum noted that companies like Facebook, Microsoft, and Netflix already allocate digital content to users through reinforcement learning algorithms.

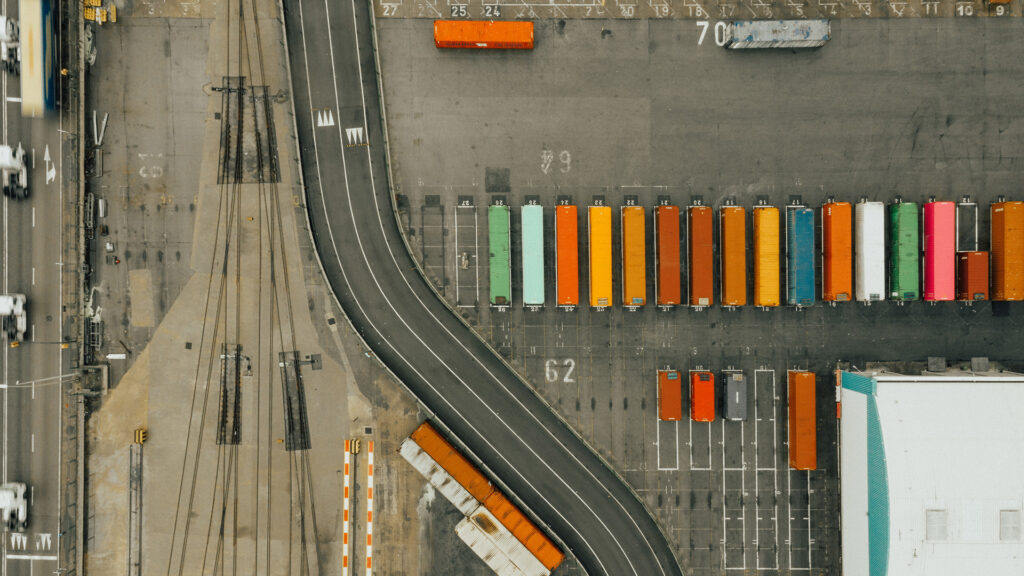

This trend is not confined solely to technology companies, as S&P Global has observed that an ever-increasing number of commodities producers and traders are making use of AI and machine learning for short-term market forecasting.1 AI is now making its way into many traditional industries, including the energy, resources and commodities sectors, with businesses seeking to utilise its power to realise production efficiencies and supply-chain optimisation. Whilst this is an exciting innovation, the exponentially increasing use of AI as part of daily commercial processes may bring with it some serious consequences.

At present, even the use of non-AI-powered automated systems may result in serious unforeseen consequences. A good example comes in the case of Quoine Pte Ltd v B2C2 Ltd [2020] SGCA(I) 2 (Quoine), in which trades of crypto assets were executed using automated trading software, without any direct human involvement, through a deterministic approach. A technical issue with the software temporarily prevented the trading platform from being capable of accessing external market data to generate new orders, ultimately resulting in 13 disputed trades being concluded, whereby one of the parties’ crypto assets were sold at a very significant undervalue.

The software used in Quoine was purely deterministic and relied on external parameters and rules coded directly into the software. As a consequence, it was easier to identify human error, albeit located in complex code, when assessing liability. In comparison, AI is theoretically able to make decisions in a fully autonomous manner with minimal external input – and it is ultimately an imperfect and experimental piece of technology and may be liable to make mistakes, which in turn may have disastrous consequences. For example, content generated by AI may be inaccurate, hallucinatory, biased or even offensive. The risk of such issues is particularly prevalent in the commodities sector, where the integration of AI has been continuing at a fast pace, both to improve business efficiency and to develop a trading edge by having more analytical power than competitors.2

Imperfect outcomes pose a variety of risks to various considerations such as safety (both physical and cyber), fundamental rights, and economic stability (collectively referred to as Rights). A pertinent question becomes, once there has been a breach of these Rights leading to harm, who bears the liability?

In order to answer this question, we have taken a broad look at how various jurisdictions around the world are approaching this issue and have summarised several possible approaches. The increasing number of technology contracts being entered into around the world will lead to a greater number of AI-driven decisions and inevitably, more disputes will arise. Greater clarity will emerge as these disputes are determined by courts and tribunals globally.

Which parties are involved in the use of AI for business?

Most commonly, the various parties involved in the development and integration of AI are:

- The developer: the entity responsible for the coding, development and training of the AI (the Developer). The Developer may also be involved in the integration, but not the use of the AI by any subsequent company relying on the model. In some cases, the Developer may be part of the in-house development team of an integrating company.

- The company integrating the AI: the party that undertakes the implementation and integration of the AI into its systems (the Integrator or Integrating Company). Common examples include the integration of AI into a manufacturing company’s assembly lines, or as part of a customer feedback process on a company website.

- The end-user: assuming that the AI has been integrated directly into a customer-facing role, the end-user would be the party that enters the prompt and receives the output (the Customer End-User). This entity may also be the company itself, if the AI is being used internally (the Company End-User).

These parties represent the various bodies either upstream or downstream in an AI life cycle. Collectively, we refer to them as the Interested Parties.

It will be immediately apparent that there are often multiple parties involved in the creation, implementation and use of an AI. In this article, we assess the liability of the Developer and the Integrator where AI-generated decisions have impacted a party’s Rights.

How may liability accrue for each of the Interested Parties?

We set out below several examples of fault-based approaches to liability, including negligence, breach of contract, or under consumer protection legislation. Clearly, such an assessment cannot cover any and all possible causes of action. For example, the European Parliament has suggested that a two-stage framework should guide questions of liability:3 (a) strict liability for operators of “high risk” AI (AI having significant potential to cause damage); and (b) a fault-based assessment for operators of any other AI.

- Consumer End User to Integrator

First, we consider cases in which negligence is a cause of action between the Interested Parties. Generally, in order to establish negligence under common law legal systems, one must show that a duty of care exists; that there has been a breach of that duty; and that the breach caused loss.

Example: Customer End-User relies on the inaccurate responses of an AI chat bot of the Integrator.

| Scenario | Parties | Liability |

|---|---|---|

| A Customer End-User relies on the answers to its queries given by an AI chat bot of an Integrator, in requesting assistance with obtaining a refund. The answers given by the chat bot are inaccurate and the Customer End-User is denied a refund. |

1) Customer End-User 2) Integrator |

The central issue here is whether an Integrator should be held liable for mistakes generated by an AI chat bot deployed on its website. |

| Case law: The same question was recently answered in the case of Moffatt v Air Canada [2024] BCCRT 149 (Moffatt) in which the Court held that, “…given the commercial relationship as a service provider and consumer…“, Air Canada owed Moffatt a duty of care and had breached its duty, resulting in its liability for negligence.In the case of State Farm Mutual Auto Insurance Co v Bochorsf [1972] 453 F.2d 533 (State Farm), the US Courts held that there would be no issue in attributing the action of the business’s computer to the business. The Court observed “Holding a company responsible for the actions of its computer does not exhibit a distaste for modern business practices. . .a computer operates only in accordance with the information and direction supplied by its human programmers. If the computer does not think like a man, it is man’s fault“. | ||

| Key Takeaways: In coming to the above conclusion, the Canadian Court held that Air Canada (the Integrator) was responsible for all information provided to a consumer (the Customer End-User). The chat bot was not a separate legal entity and formed part of Air Canada’s website. The responsibility for its actions and the accuracy of its statements rested with Air Canada. Integrators should be mindful that they may be liable in negligence for any AI generated content or advice provided on their websites. | ||

This outcome is consistent with a European Parliament Resolution of 20 October 2020, which suggests that the Integrator (who is, “…in control of the risks connected with the [AI] and who benefits from its operation in the context of a particular activity…”), should be the party to bear the burden of liability at first instance. As is demonstrated by cases such as Moffatt and State Farm, where the Customer End-User acts on faulty information, courts are likely to find that it is the Integrator who should be held responsible for negligence.

We note that it would appear challenging for Integrators or Company End-Users successfully to bring claims of negligence against Developers, unless they are able to show that the Developers owed them a duty of care, and that such duty was breached. Ultimately, the ability to apportion liability to Developers would rest on the relevant industry standards of care, and whether the specifications of the AI used satisfied that industry’s standard of care.

- Integrator to Developer

Secondly, we consider whether claims for breach of contract are useful methods for apportioning liability in respect of AI-driven decisions. Breach of contract disputes are more likely to arise between Integrators or Company End-Users, on the one hand, and Developers, on the other.

Example: Failure of an AI within a supply chain optimisation system for physical commodities.

| Scenario | Parties | Liability |

|---|---|---|

| An Integrator is provided with an AI by a Developer, for the purposes of integration into a supply chain optimisation system for physical commodities, for the automated generation of delivery, loading or shipping schedules for coal. However, the system does not perform to expectations and instead, provides inefficient delivery and loading schedules. As a consequence, shipments are delayed, or vessels sail partially empty, incurring deadfreight. The Integrator now faces claims from Customers. |

1) Integrator 2) Developer |

Contractual liability at common law requires that the loss must not be so remote as to be unrecoverable. Assuming the AI is required to perform certain tasks up to a previously established threshold, there is a potential breach of contract claim, provided loss is suffered. However, there are issues with such an approach. In particular, the autonomous nature of AI makes it challenging to ascertain whether the unexpected breach actually stemmed from the Developer. |

| Case law: This question has not yet been tested in common law jurisdictions around the world. | ||

| Key Takeaways: Developers may consider including in their contracts clauses excluding liability for defective decisions on the part of any AI. Notwithstanding the fact that such clauses have not been tested in court, it would be prudent to include as many protections as possible, given that this is experimental technology. However, in a setting such as the scenario described above, the party relying on any exclusion of liability clause would need to consider whether such a clause would be caught by legislation such as the Singapore Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977, if the purchasing party can show that it was acting as a consumer.4 Parties should closely scrutinise their software contracts and consider the medium by which they receive their AI or technology tools. By way of example, a commodity trading house would need to consider if the generative AI it uses to determine delivery of goods has been integrated by way of a new server, or if the AI has only been integrated via download. This difference in the method of integration could have ramifications as to whether the parties can only rely on a breach of contractual terms, or if they are also able to rely on further SOGA protections. | ||

While untested,5 the breach of contract approach does provide a potential avenue for Integrators to take Developers to task over the issue of defective AI. Conversely, Developers would be aiming to exclude liability for any defects as far as possible.

- Customer End-User to Integrator and Developer

Thirdly, we consider whether consumer protection claims would offer assistance for Customer End Users in the event of a defective AI decision. In jurisdictions with comprehensive consumer protection legislation, it might be possible to ascribe liability for defective AI-driven decisions to Developers as well as Integrators. For example, in the UK, the Consumer Protection Act 1987 (the UK Act) allows such redress for Customer End-Users if they can show that the product was defective and that the defect caused damage (presently limited in scope to death, personal injury or the loss of or damage to any property). This would allow a Customer End-User to pursue legal action against the Developer, notwithstanding the absence of privity between the parties. In theory, the Customer End-User may be able to rely on consumer protection laws to commence actions against the Integrator as well, which would run in parallel to any tortious or contractual claims.

However, there are limits to consumer protection legislation. For example, the UK Act does not apply in commercial contexts, so a Company End-User would not be able to pursue a Developer directly. Additionally, section 5 of the UK Act precludes claims for pure economic loss, so that evidence of defects and physical damage would be required. This would be hard to prove for the majority of Customer End-Users.

In an uncertain world, is it possible to deal with liability pre-emptively?

The law on AI is still evolving. However, there are several potential routes for parties to protect themselves and to mitigate the risks of bad AI-driven decisions. These include:

a. Customer End-Users and Company End-Users:

- Obtain end user manuals from Developers or Integrators which clearly explain how the technology works, the possible AI-generated decisions, and possibilities for misuse.

- Cross-reference and check the output of any AI-generated content.

b. Integrators:

- Implement safety checks and robust quality checks to ensure that output is accurate and reliable.

- Obtain insurance coverage to mitigate potential financial liabilities where AI-related risks materialise.

- Consider using some of the frameworks for integration and adherence to governance that have implemented around the world.

- Include warnings against hallucinatory output.

c. Developers:

- Conduct robust quality checks and audits to ensure AI systems are accurate and reliable.

- Include exclusion of liability clauses and / or warranties in any licensing contracts.

- Consider using some of the frameworks for integration and adherence to governance implemented around the world.

- Include warnings against hallucinatory output.

Conclusion

Going forward, as AI develops and becomes increasingly autonomous, a growing number of thorny questions are likely to arise. A good example is whether an AI should itself be considered an independent legal entity, not unlike a company. This question has already been posed in relation to Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAOs), which are in essence built and operate on automated rules encoded in smart contracts, stored and executed in blockchains thereby mitigating the need for human input. The increasing capabilities of AI that are able to mimic human thought processes and tasks begs the question of whether such AIs are worthy of legal protection. This has not yet been addressed by the courts, but governments and regulators appear unwilling to consider such a step. For example, the European Parliament rejected the proposal to grant legal personality for AI, stating that any legal changes should “start with the clarification that AI systems have neither legal personality or human conscience”.

Regardless, it is clear that the increasing volume of AI technology, and the integration of such technology into existing businesses, will have significant ramifications for global supply chains. Within the commodities sector alone, the uptake of AI is reaching nearly 50% of the industry.6 Presently, the majority of disputes involving AI have addressed questions of trademark and copyright.7 However, we anticipate that the number and type of technology and AI disputes will increase dramatically, as the world continues the rapid adoption of often experimental AI technology. In our view, such disputes are likely to fall within the frameworks described above, allowing parties to adopt a “first principles” approach towards the resolution of disputes, by way of contract, tort, or consumer protection. As such, the combination of a strong understanding of industry, such as the commodities sector, coupled with an understanding of how AI operates and was intended to operate in specific circumstances, will become critical skillsets in the effective resolution of AI related disputes.

Footnotes

- INTERVIEW: Commodities producers join ranks of AI users to enhance decision-making: ChAI CEO | S&P Global.

- Artificial intelligence: Commodity traders bet on big data and AI.

- Resolution 2020/2012(INL) on a Framework of Ethical Aspects of Artificial Intelligence, Robotics and related Technologies; Resolution 2020/2014(INL) on a Civil Liability Regime for Artificial Intelligence; Resolution 2020/2015(INI) on Intellectual Property Rights for the development of Artificial Intelligence Technologies.

- Singapore Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. (NB this legislation does exclude international supply contracts by virtue of section 26.) In certain circumstances, commercial parties can step into the shoes of a consumer – see R & B Customs Brokers Co Ltd v United Dominions Trust Ltd [1988] 1 WLR 321 and Dathena Science Pte Ltd v Justco (Singapore) Pte Ltd [2021] SGHC 219, in which Dathena, a business, was found to be a consumer.

- The developers suing over GitHub Copilot got dealt a major blow in court | The Verge

- INTERVIEW: Commodities producers join ranks of AI users to enhance decision-making: ChAI CEO | S&P Global.

- Generative AI Lawsuits Timeline: Legal Cases vs. OpenAI, Microsoft, Anthropic, Nvidia, Perplexity, Intel and More – Sustainable Tech Partner for Green IT Service Providers.